Over 80 years ago, as the flames of the War of Resistance Against Japan were about to spread to Zhejiang University's campus, how did the university's faculty and students choose to respond to the impending danger? The fate of individuals, the survival of the university, and the destiny of the nation all hung by a thread. How did those at Zhejiang University at the time make their decisions? How did they act? How did they embark on the long and arduous journey westward?

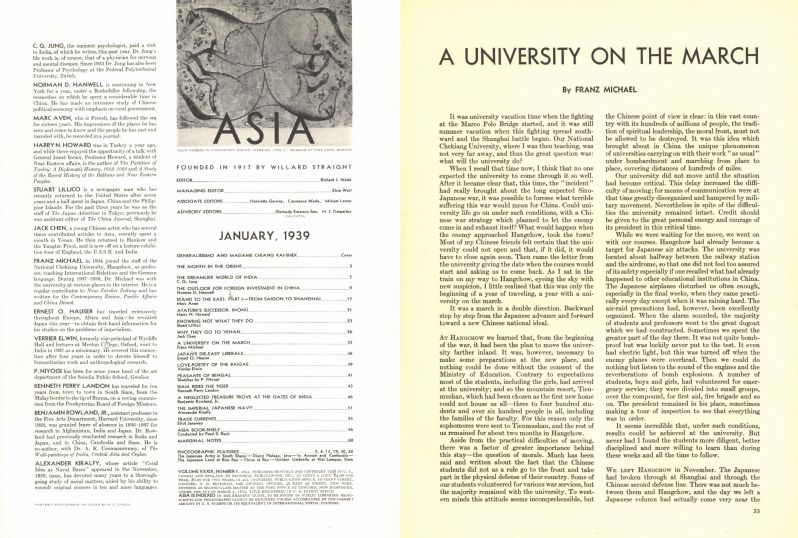

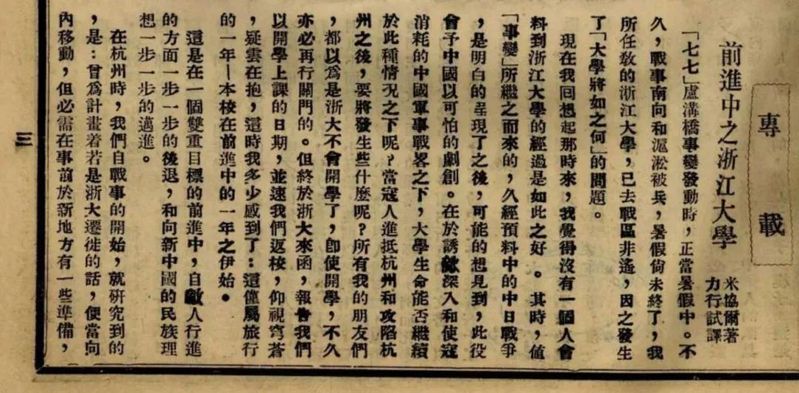

In January 1939, the Asia magazine published an article titled A University on the March, written by Zhejiang University's foreign teacher Franz Michael. Through this piece, Michael depicted the spirit of Zhejiang University's faculty and students as they bravely faced adversity, worked diligently, and remained devoted to their homeland while relocating westward to continue their education and research. This article was later translated into Chinese and was reprinted in the National Zhejiang University Bulletin on March 13, 1939.

Recently, Zhou Zhengyuan, a master's student from the 2021 cohort of the Broadcasting and Television program, traced the article's historical background and, through overseas channels, located a collector in the United States who possessed a copy of the magazine. Zhou purchased the magazine and donated it to the Zhejiang University Archives, where the original English text and magazine issue are now being displayed for the first time.

As Michael declared to the world, "It was a march in a double direction. Backward step by step from the Japanese advance and forward toward a new Chinese national ideal."

What will the university do?

In 1937, the Japanese invaders aggressively launched the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, marking the full-scale outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. As the flames of war spread southward and the Battle of Shanghai broke out, Zhejiang University, located not far from the front lines, found itself in a perilous situation. At this critical juncture, the university faced a significant choice: where would the university go from here? How would the cultural heritage of the Chinese nation continue?

Franz Michael, in his article, took a clear stance, writing:

“But the Chinese point of view is clear: in this vast country with its hundreds of millions of people, the tradition of spiritual leadership, the moral front, must not be allowed to be destroyed. It was this idea which brought about in China the unique phenomenon of universities carrying on with their work ‘as usual’ under bombardment and marching from place to place, covering distances of hundreds of miles.”

Step by step, retreating to regroup and conserve strength, enduring hardship yet never losing their unwavering resolve—that was the answer given by all the faculty and students of Zhejiang University through their actions.

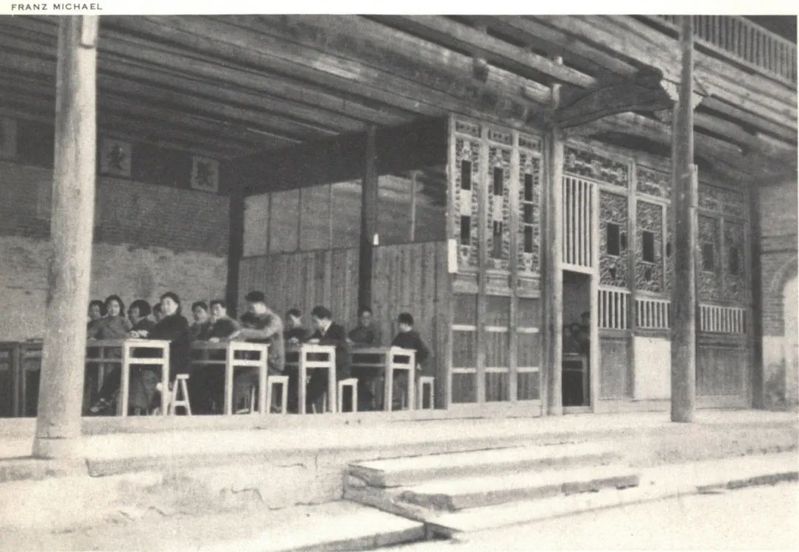

At the beginning of the relocation, Hangzhou had already become a target for Japanese air raids. Despite frequent interference and bombings by enemy planes, the university's teaching never ceased, and impressive educational results were still achieved. Franz Michael commented, “But never had I found the students more diligent, better disciplined and more willing to learn than during these weeks and all the time to follow.”

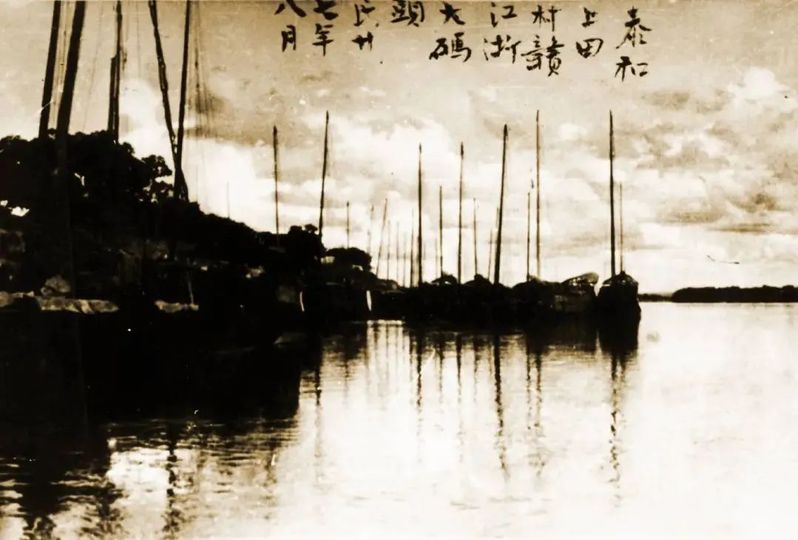

In November of the same year, to avoid further devastation, Zhejiang University began its evacuation from Hangzhou, marking the beginning of the long journey westward. By then, the advance units of the Japanese army had already approached the outskirts of the city, and the university's buildings were either destroyed or turned into military barracks for the Japanese troops. Second-year students were relocated to Tianmu Mountain as planned, while the rest of the faculty and students squeezed into cramped and difficult transportation, making their way to Jiande.

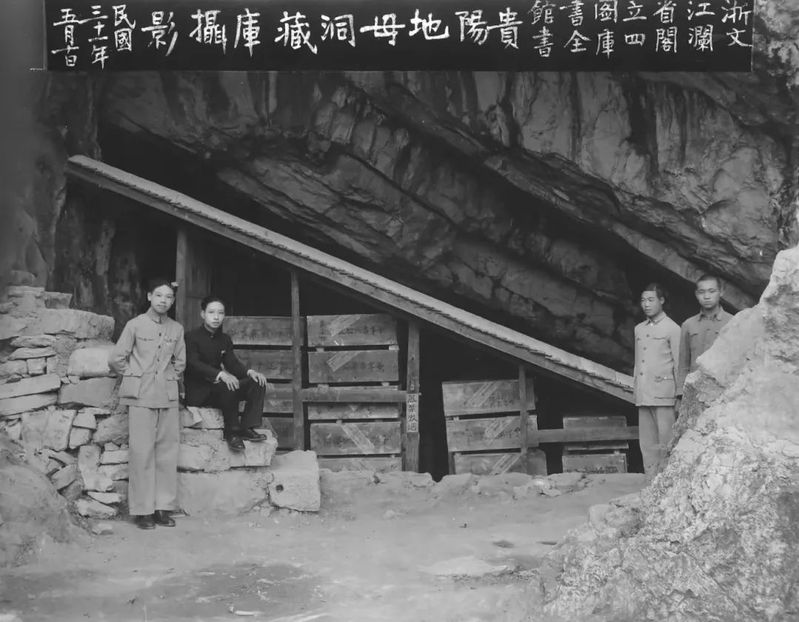

Despite enduring hardships, including sleeping outdoors and enduring the fatigue of long journeys by boat and vehicle, Zhejiang University successfully salvaged most of its educational materials—We could, of course, take only a part of our personal belongings, but the university managed to save most of the working material such as, for instance, the chemistry and physics laboratories, all the foreign books in the university library and the most valuable third of the Chinese books. . In the face of national invasion and oppression, these materials represented the hope for continuing education amidst adversity and the university’s commitment to its academic mission, even in the midst of war.

During their time in exile, the teaching environment was extremely rudimentary. Temples and ancestral halls were converted into classrooms and dormitories; inside the classrooms, all that existed were simple wooden partitions, benches, tables, and blackboards. This is a humble room, but my virtue fills it, as the saying goes. Despite the harsh conditions, the spirit of teaching and learning never wavered. The enthusiasm for research and study among the faculty and students only grew stronger. Michael once lamented, Thus proving that a university does not depend on buildings and comfort but simply on the spirit of teachers and students and a minimum equipment.

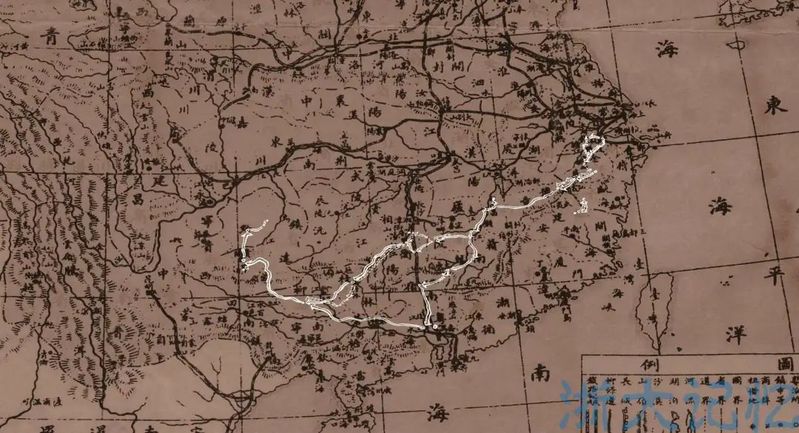

Zhejiang University, a university on the move, passed through six provinces: Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Guizhou, covering a distance of 2,600 kilometers, enduring countless days and nights of wind, rain, and hardships. The flames of war raged, the land was shattered, and the fate of individuals may have seemed as insignificant as grass in the wind; yet, there was always a group of people who chose to carry the torch of education. They traveled across half the country with their flesh and blood, shouldering the mission of academic continuity, and marching toward a new national ideal.

The people of Zhejiang University never lost their confidence. Even in the midst of a broken land, the backbone remained strong.

Traveling had made them more mature.

Personally entering the rural society of China and accepting the harsh fate of displacement, the faculty and students of Zhejiang University, during their westward relocation, shed their naivety and literary airs. They saw the beauty of the countryside through which they traveled, learned of the difficulties and problems of their fellow-countrymen; they observed the misery brought about through the war, they had been in danger themselves, truly connecting their personal destinies with the nation's fate, standing shoulder to shoulder with the vast masses of people, sharing hardships and struggles.

In A University on the March, Franz Michael also wrote about many of his observations:

When they arrived in Shantian Village, Tahe, Jiangxi, the flood was rampant, so the faculty and students of the Department of Hydraulic Engineering personally designed dikes and participated in the construction. They established Chengjiang School in a remote rural area, providing good education for both the children of the university staff and local villagers. They opened a reclamation farm in Sha Village, independently started a newspaper, and medical staff traveling with them provided public health education and free medical treatment to improve local health conditions and living standards...

The baptism by the flames of war was certainly harsh, but it was also a precious trial, as Michael said, “It was certainly a unique experience for the students... Traveling had made them more mature.”

Having experienced war, the faculty and students of Zhejiang University became even more eager for national strength and educational prosperity. If war forged the bones of China, then culture became the blood and flesh that gradually filled them. During the westward relocation, Zhejiang University added courses in Chinese literature, history, geography, and more, in the past that China can find the foundation for a new belief with which it will build up a new Chinese nation, delving into the soul of the nation buried deep within its culture.

Forward, onward—what moved forward was not only the westward migration route but also the spirit of Zhejiang University. Zhejiang University is again on the march... China is on her way. Who knows where the march will end? In early 1940, the faculty and students of Zhejiang University reached Zunyi, Guizhou, and continued their educational mission there for seven years. The westward migration had reached its final destination, but the exploration of Zhejiang University people, taking the world as their responsibility, with truth as their foundation, would not stop.

More than 80 years ago, despite hardship and adversity, the people of Zhejiang University did not cease their drive for innovation and unity. They preserved the torch of education, spread the seeds of science, and nurtured renowned research achievements along the way, leaving a profound impact on local areas.

Today, the enduring spirit of the Cultural Long March continues to glow brightly along the Qiantang River. The pioneering and innovative spirit of Zhejiang University people, driven by the pursuit of truth, is more prominent than ever. In this new era of technological transformation, Zhejiang University continues to adhere to the Four Orientations, integrating education, research, and talent development, with an increasingly firm resolve to serve the great cause of the nation.